I first got really into Dylan around 2016. I had just started learning the acoustic guitar, and I found Dylan’s songs, with their basic chord patterns, relatively easy to play. What’s more, the texture of my voice seemed to match his: nasally and unrefined, suitable for folk and not much else. I could match most of his melodies, despite having limited vocal range. I would bang out “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” in the kitchen, singing my heart out, and call it halfway decent (while irritating my housemates). Sometimes, while making dinner, I would play a YouTube mix of Dylan’s greatest hits, particularly enjoying “Jokerman,” “Visions of Johanna,” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” I had already been writing poetry for years before I ever picked up the guitar, and I immediately recognized Dylan as a fellow poet, someone for whom words are a way to give shape to the world and all of its fears, anxieties, and — yes — hope. “Blowin in the Wind” was the first song I recorded myself singing and playing on guitar. It must have been 2017 or thereabouts, and I remember coming up with a fingerpicking pattern to frame the verses. The words of that tune, it must be said, are just as relevant now as they were in the 60s: “How many times must the cannonballs fly, before they’re forever banned?”

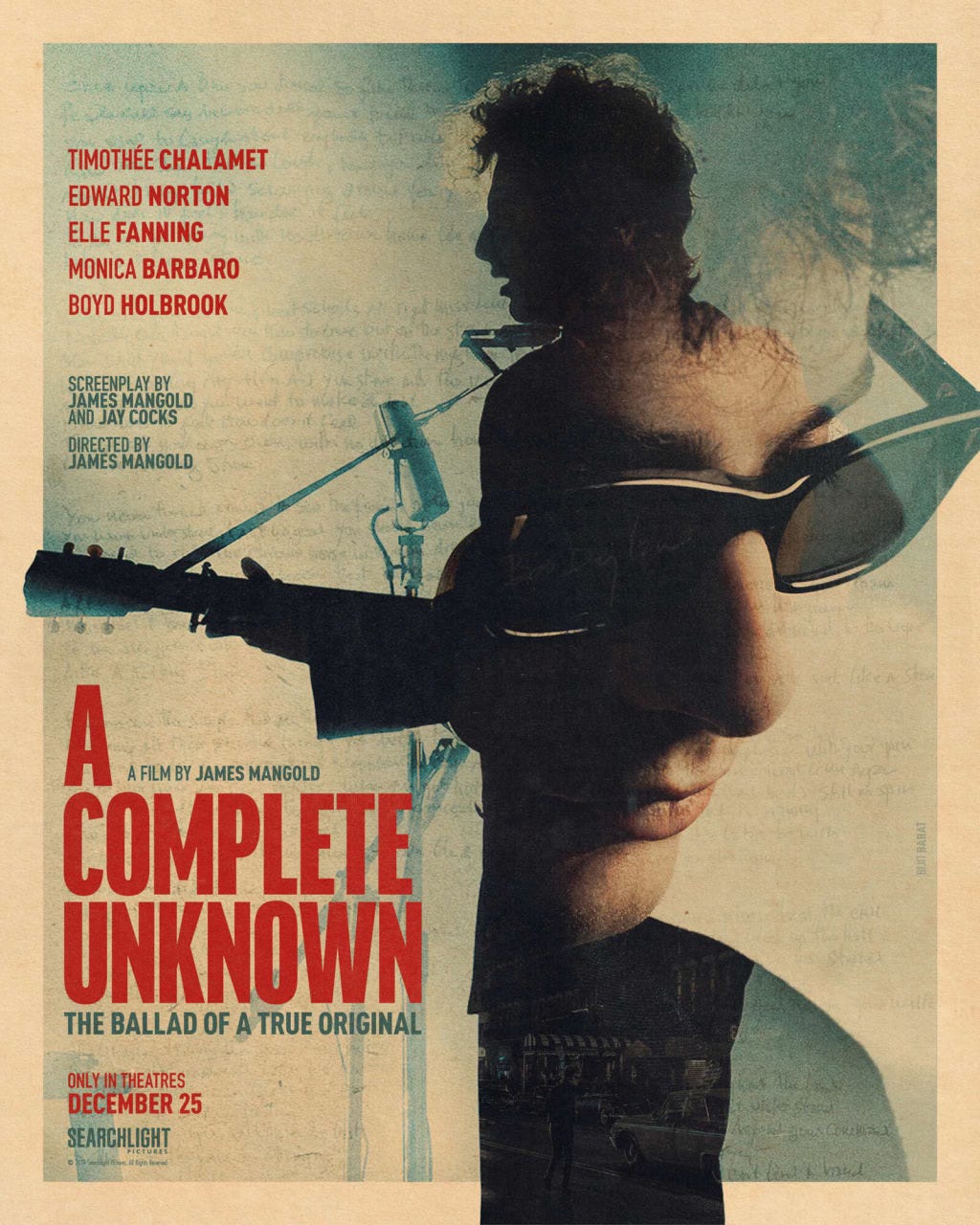

Naturally, it was with much anticipation that I walked into an arthouse theater in Tacoma with my family to watch A Complete Unknown. Directed by James Mangold (who also helmed Logan, one of my favorite comic-book movies), the film chronicles Dylan’s transformation in the early 1960s from an unknown Minnesotan boy to a cultural tour de force. In the process, Dylan struggles to discover his own identity as a musician and separate himself from the expectations of the folk movement.

On its surface, Dylan’s evolution from 60s folk icon to rock and roller seems like a rather trivial thing to dramatize. When, in the film’s climax, Dylan is getting booed and condemned as a “Judas” at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, I couldn’t help but think of the far weightier matters our country was dealing with at the time: expanding social and political rights for women and African-Americans, staring down the possibility of nuclear apocalypse, and tragically expanding our military’s entanglement in Vietnam. Nevertheless, the central drama of A Complete Unknown touches on the universal theme of individuality versus conformity, and for that reason I found Dylan’s arc in the movie compelling.

Dylan at first seeks acceptance from leading icons in the 60s counterculture, chiefly Pete Seeger (played by Edward Norton) and Joan Baez (brilliantly brought to life by Monica Barbero). These two quickly recognize Dylan’s talent and support his rising national profile, seeing him as a poster child for their movement. Some of the movie’s best scenes feature duets between Chalamet and Barbero, which crackle with obvious chemistry. Once Dylan achieves fame, however, he experiences a sense of alienation and questions whether or not he is truly the countercultural icon that everyone thinks he is. This introspection leads him to experiment musically, taking his cues from blues and electric rock, and he completes his transformation in the film’s most pivotal scene: debuting a new, electrified sound in Newport, to the horror of Seeger and many folk diehards in the crowd. The coda of the film features a touching final scene between Dylan and Woodie Guthrie, in which Dylan bids a final goodbye to the icon of folk and rides away on his motorcycle. Anyone who has been influenced by the past but aspires to break from it can identify with this sort of evolution, and the film ably portrays Dylan’s restlessness, self-reflection, and eagerness to find his place in the world.

Another major theme in the movie is the personal sacrifice required for success, and the egotistical turn that so many take as a result of fame. Mangold hones in on Dylan’s on-again, off-again romance with Sylvie Russo, a stand-in for the real life Suzie Rotolo, the girlfriend immortalized on the cover of Dylan’s 1963 album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Dylan shows himself incapable of committing to Sylvie, leading to their final breakup in the third act. To me, the most moving scene in the film is when Sylvie watches helplessly as Dylan and Baez join forces for a duet of “It Ain’t Me Babe.” The lyrics take on a new meaning as Sylvie realizes that Dylan, like the protagonist in the song, will always remain unavailable to her, his chemistry with Baez something that she can never hope to match. Dylan is sad to see Sylvie go, but she is little more than a footnote in Dylan’s pursuit of self-actualization. Likewise, his flings with Baez give a glimpse into Dylan’s hedonism. Baez, initially enthralled by Dylan, eventually shuns him for being a self-centered asshole. Dylan, in this light, is perhaps a cautionary tale of how the pursuit of artistic mastery (or any other personal endeavor) can lead one to devalue and manipulate others.

Dylan today is an enigma, seemingly full of contradictions. He continues to put out new material and has maintained an exhaustive touring schedule, despite being in his eighties. At the same time, he famously grants very few interviews and has rejected the idea that he was “the voice of his generation.” He has even denied that his early folk songs convey any kind of political message. It is his way, perhaps, of continuing to defy others’ attempts to label him. In this sense, A Complete Unknown accurately conveys a central truth about Dylan, and perhaps about the tortured artist more broadly. Defying expectations, and constantly seeking to innovate, is what drives this type of person. Without this kind of ambition, we would not have artistic greatness, and our society would likely be poorer for it. Dylan’s story, then, is quintessentially American in its ode to rugged individualism.

While I find A Complete Unknown especially meaningful given Dylan’s prominent place in my own artistic journey, anyone who appreciates music will find much to enjoy about his movie. The performances are top-notch, particularly the vocals and guitar-playing of Chalamet and Barbaro, and the aesthetic of early 60s New York City transports the viewer back to the Greenwich Village folk scene of a bygone era. I myself am looking forward to a second viewing when the film comes out on streaming.