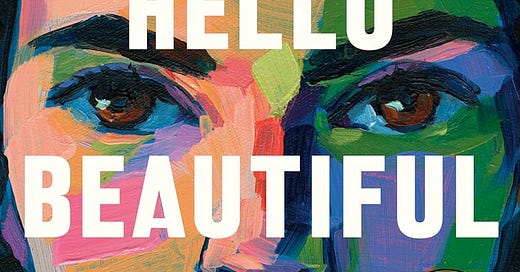

Hello, Beautiful

In this novel, Ann Napolitano weaves a multi-generational family drama of healing and reconciliation

For the last several years, I have been inspired by my wife to read more fiction. I probably finish five or six novels a year, an enterprise that has taken on new importance as I have become a fiction writer myself (my first work of short fiction, Misty the Miler, can be found here). When I read a novel now, I find myself evaluating both the story itself and the mechanics of the writing. My favorite novel, Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver, combines mesmerizing prose and punchy dialogue with an emotionally-resonant story. I see Demon Copperhead as the gold standard in modern literature, and I have inevitably compared all other novels to it ever since.

Which brings me to Hello, Beautiful by Ann Napolitano, my first novel of 2025. This is a book that I very much enjoyed, but not for the prose. I found the writing to be a little too plain in its descriptions and a little too ordinary in its dialogue. The prose lacks zing, and there is almost no attempt at humor in what is basically a somber family drama. To the book’s credit, though, the author makes up for all of this by painting a satisfying emotional arc for her characters. Each of the protagonists is fleshed out and the depths of their past traumas are carefully explored. Moreover, their thoughts and motivations are realistic given where they are emotionally at any given point in their respective arcs. I recommend Hello, Beautiful for what it says about the relational ties that bind us together, and the drastic consequences that come from cutting ourselves off from others.

The multigenerational impact of family trauma is the main theme of the novel. The book opens with William Waters, the second child of a middle-class American family that have the misfortune of losing their first child, a daughter. William’s parents never recover from the loss, and William is left with the feeling that parental love died with his sister. In college, he grafts his fate to that of the Padavano sisters, four young women from a tight-knit Catholic family in the Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago. He gravitates to Julia, the oldest, who attempts to mold and shape William into the same ambitious, upwardly-mobile professional that she herself aspires to be. William, emotionally stunted from his childhood, feels trapped by his marriage to Julia, divorces her, and attempts suicide. He survives, and in his recovery he leans on the support of his best friend, Kent, and the second eldest Padovano sister, Sylvie. Sylvie is the sensitive, whimsical dreamer who acts as a foil for the driven, hard-nosed Julia, and she forms a bond with William that eventually leads to romance and marriage. The remainder of the novel charts William’s path of self-love and self-acceptance, Julia’s challenges raising her daughter, Alice, as a single mom in New York City, and the estrangement and eventual reconciliation between Alice and her sisters.

How the decisions of one generation impact the next is a phenomenon that will be familiar to most readers. As I’ve grown older, I’ve become more aware of these interconnections. Napolitano challenges us to transcend the self-imposed limitations we place upon ourselves as a result of the messages that we receive in childhood. William is emotionally abandoned by his parents at a young age, leaving him to believe that he is both unworthy of love and incapable of showing love to other human beings. This, in turn, leads him to abandon Julia and Alice and attempt suicide. Julia, deserted by her mother and abandoned by her husband, strikes out for New York to start a new life and cuts of nearly all contact with her sisters. Alice’s universe is constrained by Julia’s self-imposed exile, and she becomes emotionally stunted and unwilling to venture outside her comfort zone and see what life has to offer her. In the end, all three characters are pushed to grow as a result of Sylvie’s terminal illness. The final scene is a conversation between William and the daughter that he never knew, with William telling Alice that he is ready and willing to help her on the road to self-discovery. The reconciliation between father and daughter acts as a fitting bookend to the story, allowing William to break the legacy of the self-hatred that he learned in his childhood.

Alice’s growth into a young adult is particularly moving for me. I see her as a near contemporary, as she is twenty-five in 2008, the same year that I graduated college. I identify with her feeling of isolation and her lack of romantic intimacy, both things that I struggled with throughout my twenties. She is terrified of pushing the boundaries of her life despite her inherent curiosity. The journey of my twenties and thirties was similar to the one that she takes in the novel: learning to overcome one’s insecurities, dive into the messiness of new relationships, and evolve as a person.

A secondary theme in the novel is the value of friendship. Those who are not family by blood become family by choice, as vividly demonstrated in William’s friend Kent. Their decades-long bond begins on the basketball court in college and continues into middle-age, with Kent providing essential companionship during William’s initial phase of intense psychiatric care following his suicide attempt. Later, William reciprocates by comforting Kent in the wake of the latter’s divorce, and Kent plays a key role in helping William prepare for and survive Sylvie’s death. Adult friendships usually take a back seat to romance when it comes to fiction, but they are vitally important in real life, and I am glad that Napolitano describes them so well here. In particular, the emphasis on male friendsships is refreshing, particularly at a time when men in our society are suffering from a crisis of loneliness.

Hello, Beautiful will not earn accolades for its prose, but the emotional core of the story makes this a worthwhile read. In the book, the sisters’ father, Charlie, uses the phrase “hello, beautiful” to affirm his daughters and signal his belief in their potential. It is a good lesson for us to follow, especially in the dark and difficult times in which we live. We could all use a little more positivity, a little more affirmation, and Napolitano admirably shows how love and vulnerability can lead us out of the darkness and towards healing.