We are now at week two. Sara and I are no longer in crisis-response mode, but are instead adapting to a new rhythm. My father and his wife visited us for five days, which helped immensely. They took two night shifts watching Harper, which allowed Sara and I to sleep uninterrupted for the first time since our baby girl was born. With their coaching, we have also managed to put Harper to bed in the bassinet, enabling her to sleep on her own (in fits and starts). If we can keep this momentum going, our hope is that Harper can sleep by herself for at least a few hours at a time on a consistent basis. This relief can’t come soon enough. Living as sleep-deprived zombie parents isn’t sustainable for weeks on end.

I am getting more and more of a perspective on parenting, as the initial shock recedes. The parenting skills that Sara and I are developing right now are, I think, universally applicable, regardless of who your child is. Chief among these skills is patience. You simply cannot get frustrated with your kid, because they are only doing what instinct tells them to do. They cry when they are scared, when they’re hungry, or when they have a poopy diaper. As I’ve written previously, you have to accept that your child will monopolize your time and test your endurance. As but one example, breastfeeding is enormously time-consuming, a fact that I didn’t understand until Sara started doing it. At Harper’s age, she must nurse every two to three hours or sometimes even more frequently (“cluster feeding”), and each session can take thirty minutes or longer, depending on how efficient she is in drawing milk. Breastfeeding also isn’t a passive activity, as we have to coax Harper to engage in “active feeding” (i.e. sucking and swallowing) rather than just hanging out passively on the nipple as a source of comfort. Because of the time investment that is required to breastfeed, and because breastfeeding does not lend itself to multitasking, I often find myself feeding Sara a meal while she is simultaneously feeding Harper, a method of efficiency maximization that illustrates how time is the most precious resource in the household economy. When you factor in the time you have to spend feeding your child, changing her clothes and diapers, soothing her to sleep, and taking her for walks outside, there is barely enough time left to accomplish everything else you need to do in life (personal hygiene, etc.). This truly is an endurance test like no other I have faced.

Friends and family continue to tell me that I will miss this stage of parenting, when Harper is tiny, immobile, and completely dependent on Sara and I. I’m sure this is true, even though in my mind I am conjuring up images of all the fun things we will be able to do when Harper is old enough to walk and talk. While challenging, the parenting we are doing now is relatively simple. The tasks themselves are not complex, but simply require perseverance and consistency. The really challenging stuff? That comes later, I know. Things like teaching your kids good manners, self-discipline, and resilience in the face of failure. Things like drawing boundaries and explaining right from wrong, and how to protect yourself from toxic individuals while avoiding becoming that toxic person yourself. That’s the stage where parenting strategies must diverge, given that every child’s personality is different, and given that males and females move through the world in different bodies and can therefore expect to be burdened with differing expectations.

It’s the latter observation — sex-related differences and their implications — that has given me much to contemplate over the past few months. Raising a girl brings with it unique challenges. I think that raising girls and boys is probably equally challenging, but in very different ways. With girls, the challenge for parents is to raise a balanced, self-confident, and emotionally resilient daughter who, while inevitably concerned with looking beautiful, does not derive her value purely from physical appearance. With boys, the challenge is to take masculine energy and rambunctiousness and challenge it to productive, rather than destructive, purposes. Let’s call these two things positive femininity and positive masculinity. With Harper, my wish is for her to embody the former while being able to recognize (and value) the latter.

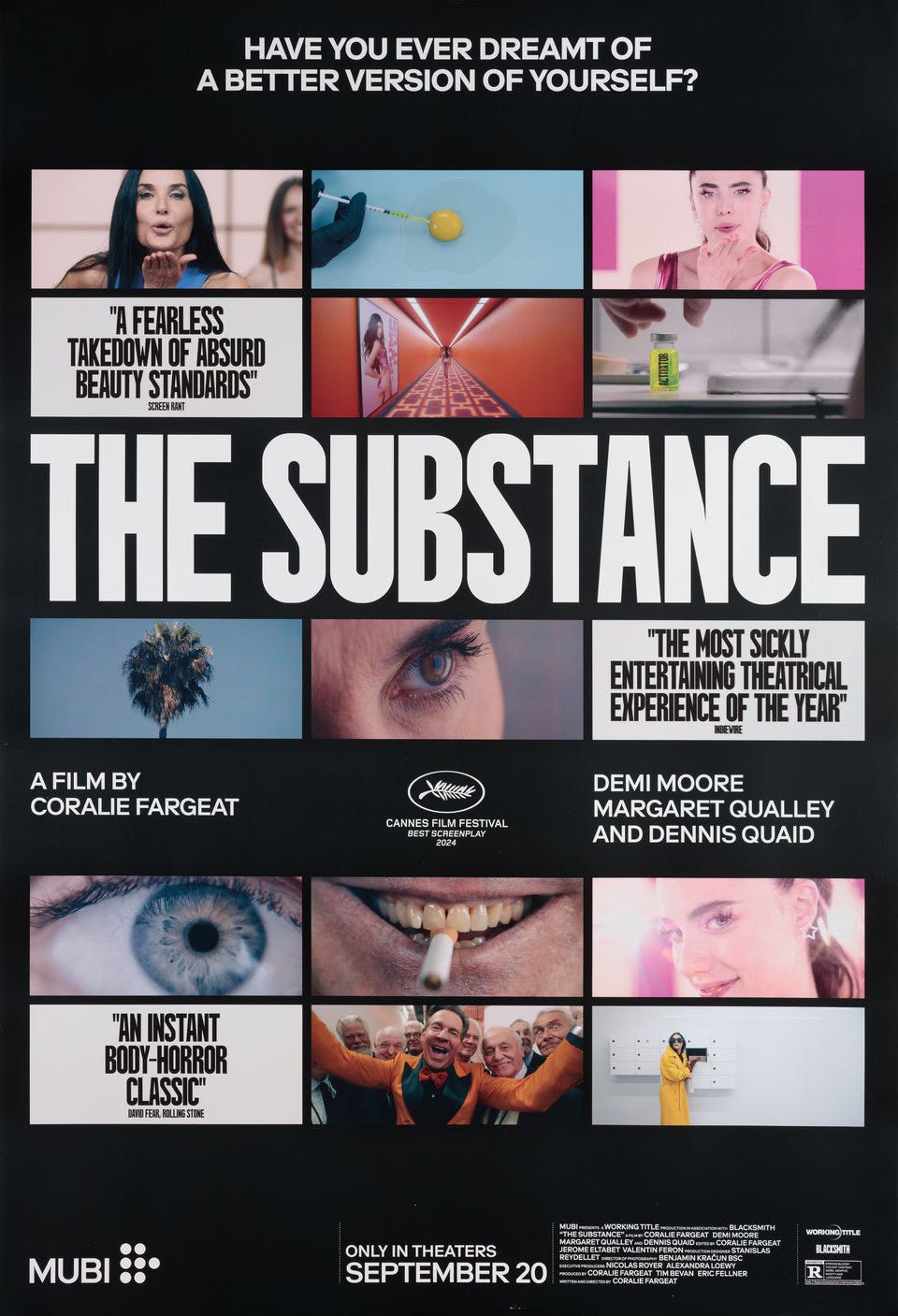

It’s perhaps ironic that one of the first movies I watched with Harper during my night shift was The Substance, a recent Best Picture nominee that also netted lead actress Demi Moore a much-deserved Golden Globe. My other choices for nighttime viewing have been more lighthearted fare — namely, Mozart in the Jungle — but I had wanted to see The Substance for some time, drawn with lurid fascination to its widely-reported gore as well as its messaging about sexism. Harper didn’t watch the movie, of course; she was simply slumbering on my lap, while I observed, transfixed, this body horror banger of a movie. I think some part of me wanted her to share in the experience of The Substance, as I knew it would help me distill some of my still-brewing thoughts about femininity and the lessons that Harper will have to absorb as a girl.

The Substance can best be described as a dark satire, featuring a stylized version of Hollywood where blatant sexism is on full display. Demi Moore plays Elizabeth Sparkle, a past-her-prime actress who is about to be fired from her popular fitness show after committing the unpardonable sin of turning fifty. Desperate to maintain her relevance in an industry (and a world) where a woman’s value is tied to youth, she is seemingly offered a solution when an unnamed corporation offers her the titular “substance,” an injectable drug that promises to create a younger, “better” version of her. After some initial hesitation, Elizabeth takes the drug, creating a younger alter-ego of herself named Sue (played by Margaret Qualley). Because Elizabeth and Sue share the same consciousness and must swap bodies every two weeks, Elizabeth can relive her glory days vicariously through Sue. The unabashedly sexy and hedonistic Sue quickly earns popular acclaim and takes over Elizabeth’s fitness show.

The director of The Substance, Coralie Fargeat, crafted the script as a parable for the emotional and physical ordeal that women endure in order to fit our culture’s idealized beauty standards. The tragedy of Elizabeth is that she seemingly has it all, and yet isn’t satisfied with her life. She is talented, beautiful, and successful. Nevertheless, she sees aging as a curse and is deeply insecure about moving on to the next stage of her life. In one pivotal scene, she contemplates killing Sue, but relents at the last minute after acknowledging that Sue is the only “part of her” that the world loves. In another scene, another substance-user admonishes Elizabeth for failing to realize that her life right now “still matters,” a reminder that aging is not the curse we often assume it is. The main takeaway of The Substance is that authentic, holistic femininity is marred by our society’s twin obsessions with youth and beauty. To illustrate this point, Sue ends up exceeding the two week limit and refuses to swap places with Elizabeth, leading ultimately to the degeneration and destruction of both bodies.

What does this have to do with parenting? I think anyone who raises a girl has to be cognizant of cultural messaging and the impact of such messaging on a girl’s self-esteem. There is an idealized image of beauty — exemplified in Sue — that Harper will inevitably feel pressure to imitate. Wanting to look and feel beautiful is not wrong in itself; indeed, a woman’s concern with her physical appearance is a cultural universal and will remain so. The danger, as with so many things, comes with obsessing over it. Elizabeth cannot appreciate the good things she has in life because she constantly compares her body to Sue’s. Self-acceptance is a key part of positive femininity precisely because it runs counter to the messaging girls receive from mass media. I know that the day will come, sooner rather than later, that Harper will be scrolling through TikTok (or whatever social media platform is in vogue at the time), absorbing everything that the world has to say about feminine beauty standards. I know that Sara and I won’t be able to shield her from these forces. Instead, we will have to provide her with the lens of positive femininity and trust her to discern and avoid the worst excesses of our culture.

The higher levels of parenting, such as teaching lessons about femininity, seem daunting from where I now stand. To borrow a karate analogy, Sara and I are using all our strength to perform well with our white belts but we will eventually have to graduate to black belt if we are to set up Harper for success down the line. I think part of parenting is redefining what you perceive as difficult while constantly leveling up your skills through experience. When we’re at the point where we are shaping Harper’s beliefs about femininity, will I reminisce about the days when parenting consisted of little more than changing diapers and managing sleep schedules? I may indeed. Even so, part of me looks forward to those conversations. A privilege of parenting is shaping another human being: physically, intellectually, and spiritually. My hope is that Harper integrates these lessons well enough to withstand the whirlwind of negativity that society will inevitably throw her way.

Wish I would've written down my thoughts and feelings like this when my kids were younger. So much changes, and it changes so fast, it's hard to hold on to your sense of the world -- your kids, your self -- from one month (and year) to the next.